Around midnight on Oct 24, while Dennis Baldocchi was sleepily re-deriving the conservation of mass equation, the AmeriFlux website released a major methane bubble and published the brand new (odorless) web presence for AmeriFlux’s first Action Theme Year—the Year of Methane! You can check out the Year of Methane objectives, projects, and collaborating partners, which I must say includes some very fine people. And regardless of your methane-measuring status, please sign up as a Participant, post your own methane confessions to the new Methane Fluxes Forum, and include #methanefluxes on all your future tweets. You know what they say: If you can name methane, you can do methane…

But—that’s wrong! If I gathered anything from our Methane Breakout Group at this year’s AmeriFlux PI meeting, it’s that there is plenty of methane work to be done. On the last day of the PI meeting, a group of 25 methanusiasts, consisting of PIs, technicians, postdocs, students, and (one) modeler, bravely traded carbon fixation for fermentation, and met to discuss how we can get closer to our goal of ‘methane fluxes, everywhere, all of the time.’

Our discussion covered many methan-ological themes including methane measurement and analysis, wetland methane and beyond, and even methanogenic microbes. The conversation will continue as Year of Methane ramps up but here are some of the highlights and take-homes:

Methane database and synthesis

The effort to compile methane flux data from across AmeriFlux (and FLUXNET) is ongoing for the next year, and beyond. To date, we’ve collected data from about 30 AmeriFlux sites and we know many more sites are making methane measurements globally. We encourage AmeriFlux PIs to submit their data so their sites can inform key data products, such as a global map of wetland methane emissions, which will improve with greater data coverage. Please feel free to contact me if you have questions about the data submission or progress on the synthesis work.

Plan your BADM

Water-table depth isn’t being measured across all wetland sites, but is likely to be an important control on fluxes. In addition, soil class, carbon concentrations, and microbial community analysis, as well as isotopes and CowCams, were all discussed as potentially useful ancillary measurements. Dario Papale updated us on the European RINGO initiative, which is tackling both BADM and flux data standardization for methane. Read more here—they encourage new participants to join – and contact Dario if interested in contributing.

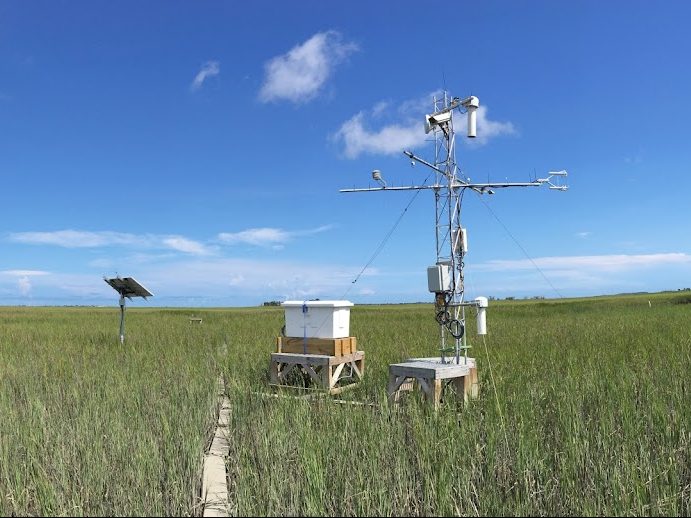

Kyle Hemes, Daphne Szutu, and Etienne Fluet-Chouinard inspect equipment and the complex canopy at the newly restored Sherman Island restored wetland (US-Sne), CA.

Hot-spots and hot-moments

A major concern researchers expressed during the breakout group for measuring methane is the flux heterogeneity that occurs over small spatial scales. If a tower footprint shifts over a different patch within a wetland system, it might see very different fluxes. One solution to this might be downscaling at the site level, which would lead to more accurate flux estimates, but also a chance for spatial attribution of different flux signals, i.e., new science! We discussed some opportunities to facilitate this, such as using the tech team’s drones during site visits as well as collaboration with NEON to produce high-resolution surface cover, or elevation, models for individual sites over the coming years. The episodic nature of methane fluxes was also discussed, such as bubble release (ebullition) events, and how a ebullition signal might be identified in flux data.

Beyond wetlands

For now, we are focused on high methane-emitting ecosystems, such as wetlands, but (1) we don’t know what we don’t measure, and (2) even no-flux is still flux-information when it comes to modeling. So we talked about the possibility of measurements over landfills, and rice and other agricultural systems. AmeriFlux has two open-path methane analyzers (LICOR 7700) available for loan, so we encourage PIs to take a look to see if their systems are methane-emitters.

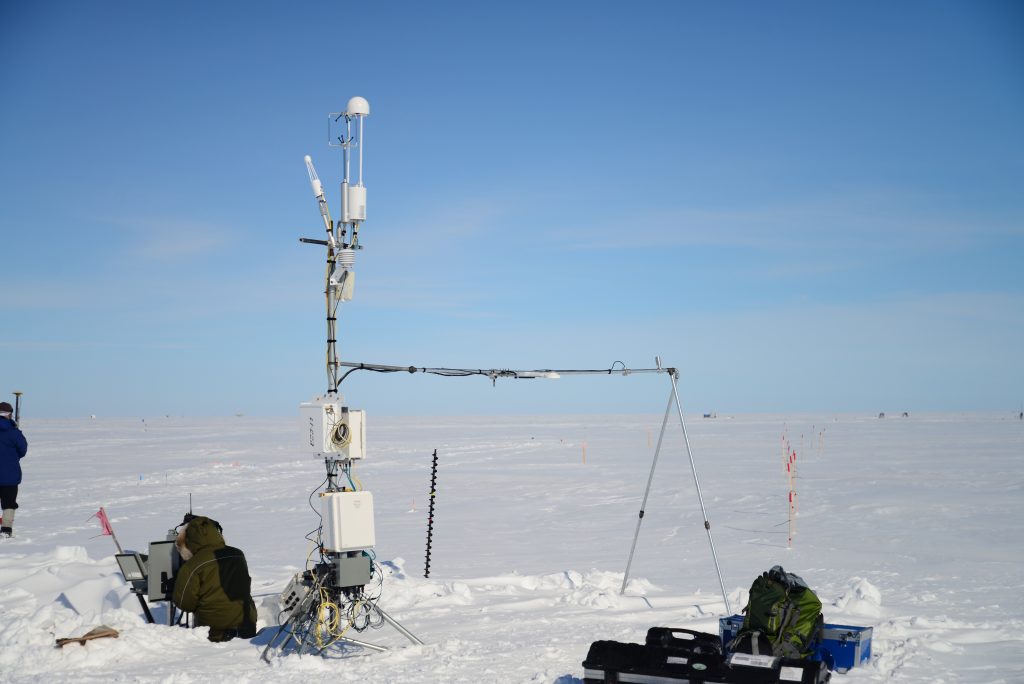

Tech team’s PECS doing Methane flux measurements, LICOR 7700, at AmeriFlux site US-HRA. Photo cr. Stephen Chan

The future lies beneath

Looking down is not normally associated with moving forward, but growing a network of eddy covariance methane observations gives us a chance to understand an important belowground component of the ecosystems we study with the same techniques we’ve used to study vegetation canopies. Moving belowground, we swap autotrophy for heterotrophy, we trade the grand RuBisCO for a plethora of endo-and exo-enzymes, and we get to study a whole new suite of largely microbial processes with all the strengths of biometeorology. There’s plenty to get excited about, and plenty to do!

Guest blog by Gavin McNicol, Stanford University

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation